The original article was published on March 13, 2025.

Hello, I'm Munetoshi Ishikawa, a mobile client developer for the LINE messaging app.

This article is the latest installment of our weekly series "Improving code quality". For more information about the Weekly Report, please see the first article.

Two close calls

The following code is a class for managing a resource. After using the resource, it is expected to call close to release the resource. If the resource has already been released when close is called, a runtime error is thrown by error.

class FooResource {

var isClosed = false

private set()

...

fun close() {

if (isClosed) {

error(...)

}

... // Release resources

isClosed = true

}

}Is there any room for improvement in this code?

Ask the same thing

To safely call close in the above code, it is necessary to check isClosed.

if (!fooResource.isClosed) {

fooResource.close()

}As the places where close is called increase, there is a possibility of missing the isClosed check, unintentionally causing a runtime error.

For FooResource.close, it would be good to make it idempotent, similar to Java or Kotlin's AutoCloseable. Idempotency means that the result of calling once and the result of calling multiple times are the same. In the following implementation, the result of calling close once and calling it multiple times is equally "release the resource and set isClosed to true".

class FooResource {

var isClosed = false

private set()

...

fun close() {

if (isClosed) {

return

}

... // Release resources

isClosed = true

}

}By ensuring the function is idempotent, you can potentially enjoy the following benefits:

- No need to perform a state check before calling the function

- The state after the function call becomes easier to predict

- The "initial state" can be concealed

Among these, the benefits of "no need to perform a state check before calling the function" and "the state after the function call becomes easier to predict" can be applied to non-idempotent functions as well. It is sufficient to change the behavior of an erroneous call to "do nothing" instead of using exceptions.

Even when returning

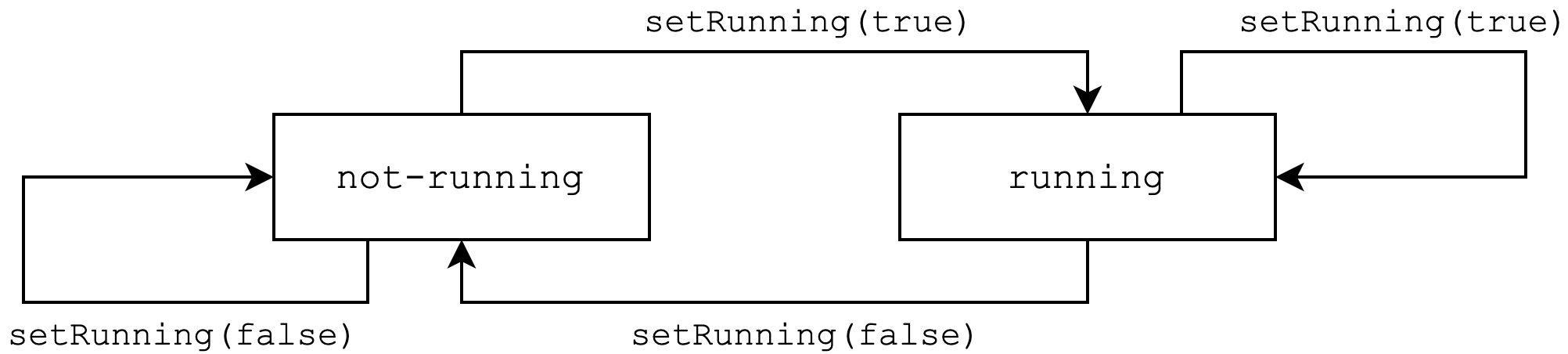

Even when state transitions are cyclic, you can leverage the two benefits of "no need to perform a state check" and "the state after the function call becomes easier to predict". The following Animation class has two states, "running" and "not-running", and can transition between them by calling setRunning(true) and setRunning(false). In this case, if setRunning(true)/setRunning(false) is called when it is already "running"/"not-running", the behavior is "do nothing".

class Animation {

private var isRunning = false

fun setRunning(isRunning: Boolean) {

if (this.isRunning == isRunning) {

return

}

this.isRunning = isRunning

...

}

}The state transitions are as follows:

In this state transition, if you consider setRunning(true) and setRunning(false) as separate functions, you can say they are idempotent functions.

By making the behavior "do nothing" when already transitioned, it becomes easier to simplify the code when multiple event handlers call setRunning. This is because it is guaranteed that the latest state is determined by the argument of setRunning regardless of the current state.

Even with three states

This concept can also be applied to three-state cases with two functions. Here are two representative examples:

- When a specific function is prioritized over other functions

- When the first called function is prioritized over other functions

When a specific function is prioritized over other functions

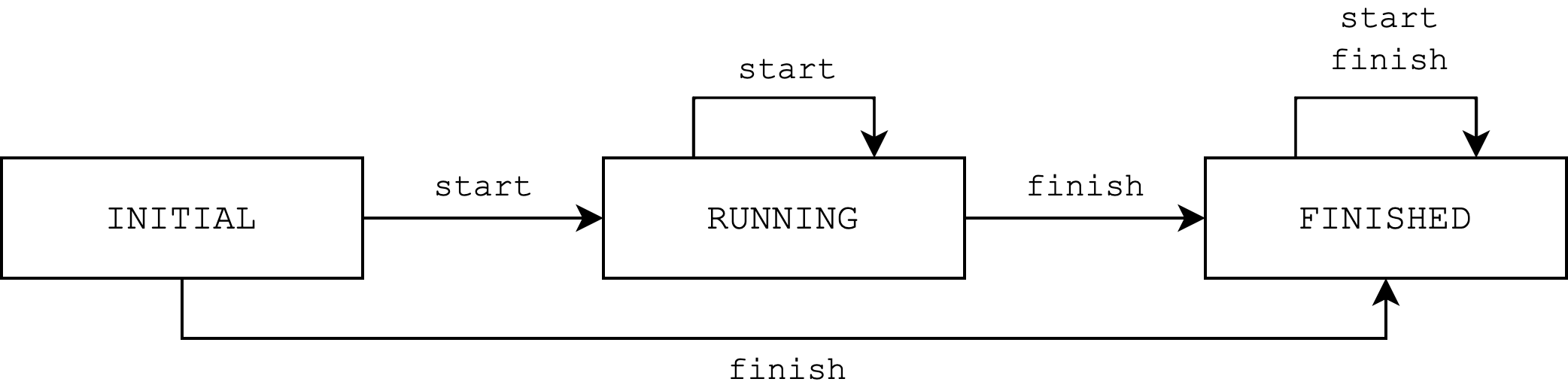

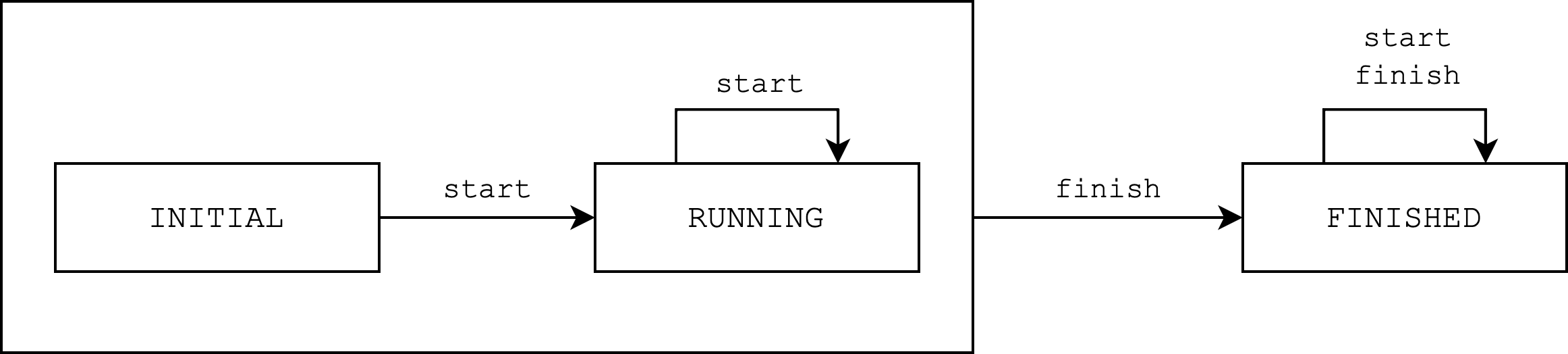

The following Task has functions start and finish, which transition to "RUNNING" and "FINISHED" respectively. However, if both start and finish are called, finish is prioritized regardless of the order.

class Task(...) {

private var state: State = State.INITIAL

fun start() {

if (state != State.INITIAL) {

return

}

state = State.RUNNING

...

}

fun finish() {

if (state == FINISHED) {

return

}

state = State.FINISHED

...

}

enum class State { INITIAL, RUNNING, FINISHED }

}The state transitions are as follows:

From another perspective, "INITIAL" and "RUNNING" form one large state, and calling finish transitions from them to "FINISHED". Under this interpretation, finish can be considered an idempotent function.

Conversely, by viewing "RUNNING" and "FINISHED" as one state, start can also be considered an idempotent function.

By prioritizing one state transition and maintaining the current state for other calls, it becomes easier to manage the lifecycle of resources or tasks.

When the first called function is prioritized over other functions

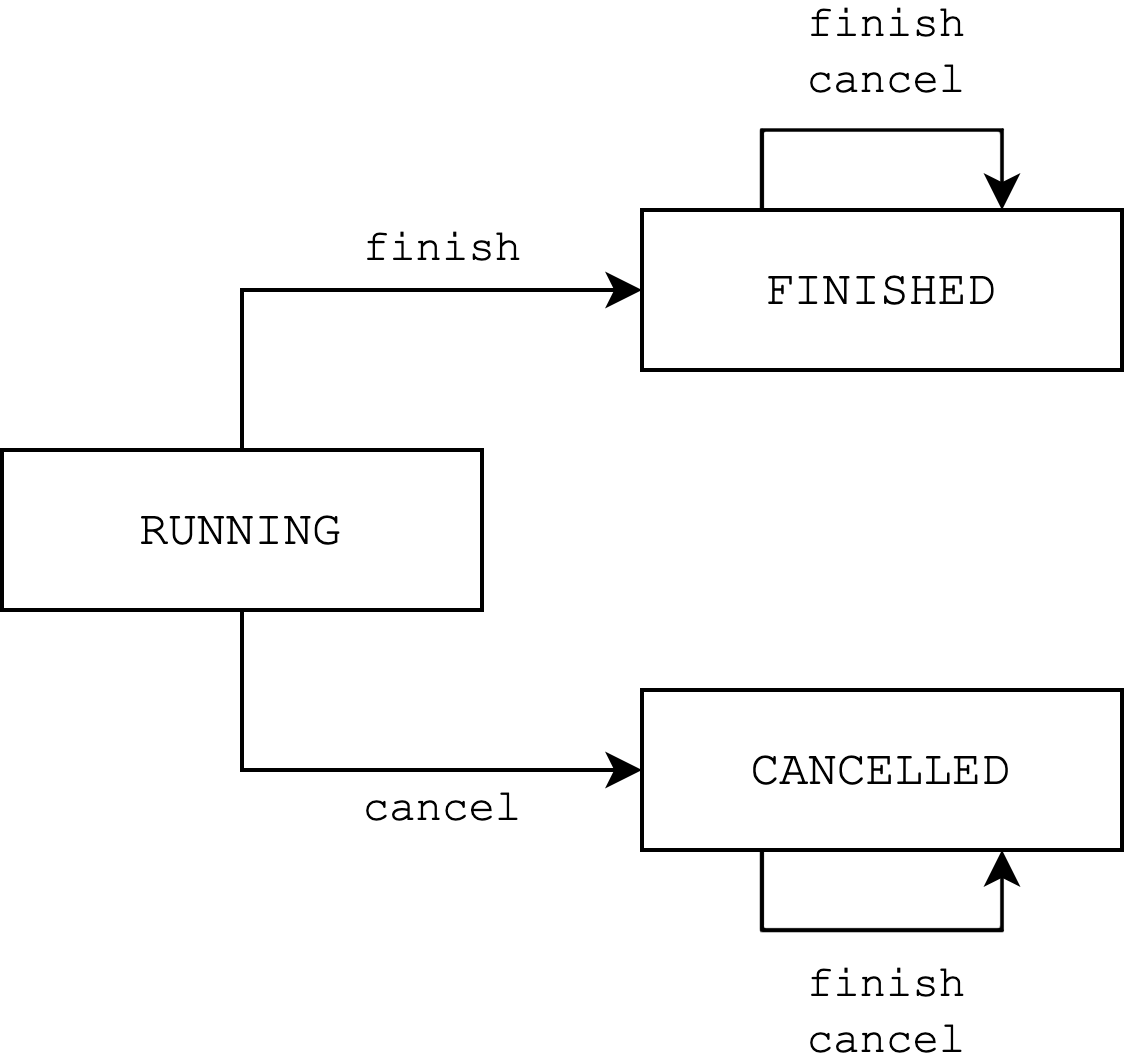

In the following Task, there is a possibility of normal completion with finish and cancellation with cancel. Unlike the previous example, it is not predetermined which of finish or cancel is prioritized; the one called first is prioritized.

class Task(...) {

private var state: State = State.RUNNING

fun finish() {

if (state != State.RUNNING) {

return

}

state = State.FINISHED

...

}

fun cancel() {

if (state != State.RUNNING) {

return

}

state = State.CANCELLED

...

}

enum class State { RUNNING, FINISHED, CANCELLED }

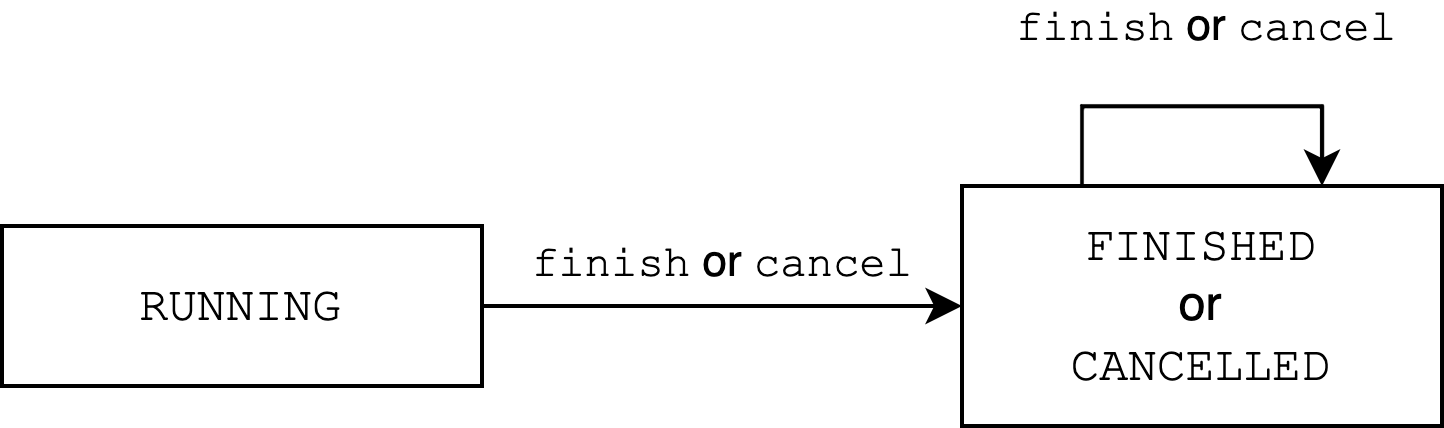

}The state transitions are as follows:

Here, by considering "FINISHED" and "CANCELLED" as one large state and treating finish and cancel as one function, the combined function can be considered idempotent.

This transition design is particularly effective in situations where different callers asynchronously call finish or cancel. For example, when finish is called upon query execution completion, but there is a possibility of asynchronous cancellation by the user at any time, there is a possibility that the other has already been called when finish or cancel is called. Even in such situations, by making it safe to call the function without checking the current state, the caller's code can be simplified.

In a nutshell

By making the behavior "do nothing" instead of throwing an exception when already transitioned, the code can potentially be made more robust.

Keywords: idempotency, state transition, error handling